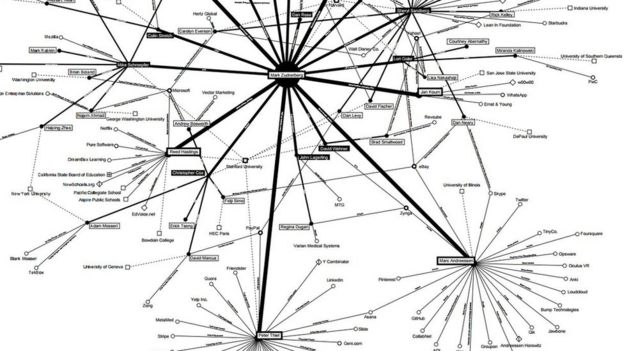

Facebook's collection of data makes it one of the most influential organisations in the world. Share Lab wanted to look "under the bonnet" at the tech giant's algorithms and connections to better understand the social structure and power relations within the company.

A couple of years ago, Vladan Joler and his brainy friends in Belgrade began investigating the inner workings of one of the world's most powerful corporations.

The team, which includes experts in cyber-forensic analysis and data visualisation, had already looked into what he calls "different forms of invisible infrastructures" behind Serbia's internet service providers.

But Mr Joler and his friends, now working under a project called Share Lab, had their sights set on a bigger target.

"If Facebook were a country, it would be bigger than China," says Mr Joler, whose day job is as a professor at Serbia's Novi Sad University.

He reels off the familiar, but still staggering, numbers: the barely teenage Silicon Valley firm stores some 300 petabytes of data, boasts almost two billion users, and raked in almost $28bn (£22bn) in revenues in 2016 alone.

And yet, Mr Joler argues, we know next to nothing about what goes on under the bonnet - despite the fact that we, as users, are providing most of the fuel - for free.

"All of us, when we are uploading something, when we are tagging people, when we are commenting, we are basically working for Facebook," he says.

SHARE LAB

SHARE LAB

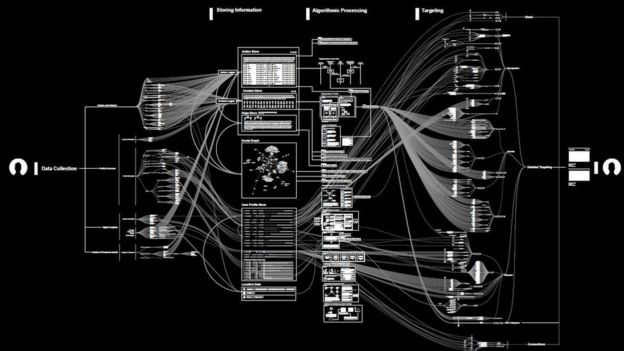

The data our interactions provide feeds the complex algorithms that power the social media site, where, as Mr Joler puts it, our behaviour is transformed into a product.

Trying to untangle that largely hidden process proved to be a mammoth task.

"We tried to map all the inputs, the fields in which we interact with Facebook, and the outcome," he says.

"We mapped likes, shares, search, update status, adding photos, friends, names, everything our devices are saying about us, all the permissions we are giving to Facebook via apps, such as phone status, wifi connection and the ability to record audio."

All of this research provided only a fraction of the full picture. So the team looked into Facebook's acquisitions, and scoured its myriad patent filings.

The results were astonishing.

Visually arresting flow charts that take hours to absorb fully, but which show how the data we give Facebook is used to calculate our ethnic affinity (Facebook's term), sexual orientation, political affiliation, social class, travel schedule and much more.

SHARE LAB

SHARE LAB

One map shows how everything - from the links we post on Facebook, to the pages we like, to our online behaviour in many other corners of cyber-space that are owned or interact with the company (Instagram, WhatsApp or sites that merely use your Facebook log-in) - could all be entering a giant algorithmic process.

And that process allows Facebook to target users with terrifying accuracy, with the ability to determine whether they like Korean food, the length of their commute to work, or their baby's age.

Another map details the permissions many of us willingly give Facebook via its many smartphone apps, including the ability to read all text messages, download files without permission, and access our precise location.

Individually, these are powerful tools; combined they amount to a data collection engine that, Mr Joler argues, is ripe for exploitation.

"If you think just about cookies, just about mobile phone permissions, or just about the retention of metadata - each of those things, from the perspective of data analysis, are really intrusive."

More Technology of Business

Facebook has for years asserted that data privacy and the security of its operations are paramount. Facebook data, for example, cannot be used by developers to create surveillance tools and the firm says it complies with privacy protection laws in all countries. Thousands of new staff have been recruited to police its content.

Mr Joler, though, while admitting that his research made him a little paranoid about the information that was being harvested, is more worried about the longer term.

The data will remain in the hands of one company. Even if its current leaders are responsible and trustworthy, what about those in charge in 20 years?

Analysts say Share Lab's work is valuable and impressive. "It's probably the most comprehensive work mapping Facebook that I've ever seen," says Dr Julia Powles, an expert in technology law and policy at Cornell Tech.

"[The research] shows in cold and calculated terms how much we are giving away for the value of being able to communicate with your mates," she says.

The scale of Facebook's reach can be stated in raw numbers - but Share Lab's maps make it visceral, in a way that drawing parallels cannot.

"We haven't really got appropriate historical analogies for the tech giants," explains Dr Powles. Their powers, she continues, extend "far beyond" the likes of the East India Company and monopolies of old, such as Standard Oil.

And while many may consider the objectives of Mark Zuckerberg's empire to be rather benign, its outcomes are not always so.

Facebook, argues Dr Powles, "plays to our base psychological impulses" by valuing popularity above all else.

ISMAGILOV

ISMAGILOV

Not that she expects Share Lab's research to lead to a mass Facebook exodus, or a dramatic increase in the scrutiny of tech titans.

"What is most striking is the sense of resignation, the impotence of regulation, the lack of options, the public apathy," says Dr Powles. "What an extraordinary situation for an entity that has power over information - there is no greater power really."

It is this extraordinary dominance that the Share Lab team set out to illustrate. But Mr Joler is quick to point out that even their grand maps cannot provide an accurate picture of the social media giant's capabilities.

There is no guarantee, for example, that there are not many other algorithms at work that are still heavily guarded trade secrets.

However, Mr Joler argues, "it is still the one and only map that exists" of one of the greatest forces shaping our world today.

No comments:

Post a Comment